Mother Tongues: On Yoko Tawada's "Scattered All Over the Earth" & Jessica Au's "Cold Enough for Snow"

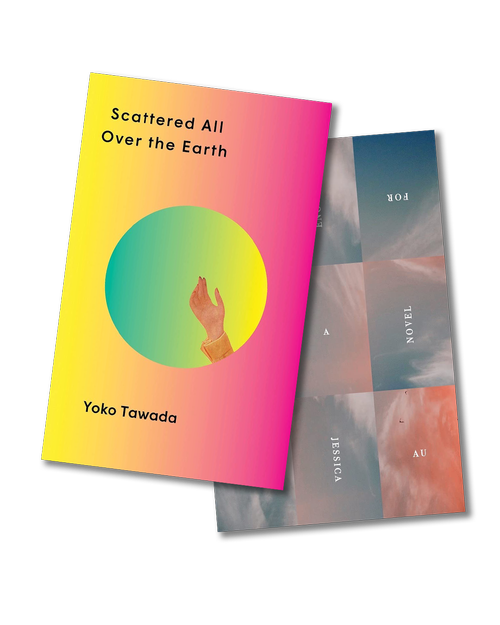

Yoko Tawada | Scattered All Over the Earth | New Directions | 2022 | 228 Pages

Jessica Au | Cold Enough for Snow | New Directions | 2022 | 97 Pages

Two new books revolve around one place. The books are Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au and Scattered All Over the Earth by Yoko Tawada. The place is Japan. In Cold Enough for Snow, the narrator meets her mother in Tokyo in the hopes of rekindling a fraught mother-daughter connection. Scattered All Over the Earth is set in a future where Japan no longer exists.

Both Tawada and Au use place as a way to write about identity over time—about the selves that inhabit the here and now, and the past selves, overlaid onto the landscape like variegated watermarks. As their characters seek connection through language in foreign countries, both authors question what it means to belong, but they frame the tension between being an insider and an outsider through opposite lenses. Scattered All Over the Earth is a broad, kooky, character-driven dystopia that revolves around Japan’s absence. Cold Enough for Snow employs subtler prose that traces the emotional associations evoked by the palpable, sensory presence of Japan.

In Scattered All Over the Earth, foreignness permeates every scene. The chapters are all first-person accounts from a crew of global misfits—migrants and exiles, foreigners and social outcasts. The central character, Hiroku, originally from Japan, left before it was mysteriously wiped from the map. The story follows her search for someone else who speaks her native language, and who might be able to give her answers about the fate of her country. The rest of the characters assemble around Hiruko’s quest, but all of them straddle the line between host and guest. One character from Pune, India, acts as tour guide for the others in Germany, where he lives; an Indigenous Greenlander pretends to be a chef from the "land of sushi" (no one calls it Japan in the book; the name seems to have been lost along with its place on the map); another Japanese émigré flees a relationship in Germany to work in France. Knut, a linguist from Denmark, falls in love with the new, singular language Hiroku has created in order to communicate with Europeans.

At its core, Scattered All Over the Earth is a climate apocalypse novel. Tuna is on the verge of extinction. Companies in Norway and California search for oil deposits in the ocean using seismic blasts, deafening and ultimately killing dolphins and whales. Meanwhile, memories of nuclear mishaps punctuate the pages, casting an environmental shadow on the unnamed disaster that ravaged Japan. This global future—and its transparent political commentary—also represents the absurd and destructive power of global capitalism. The world is close to our own, suggesting that soon our boundaries will radically change. Tawada reminds us that we, too, might become refugees from lands that no longer exist—obliterated by nuclear mishaps, rising water levels, or arbitrary lines drawn in history textbooks.

Tawada’s future is also, more subtly, about the borders between languages. Knut is drawn to Hiroku not for her looks or her charm, but for her “homemade language,” which she calls “Panska.” The language is forged from the necessities of immigration—to communicate quickly and with as many people as possible. It reads like a stuttering, imprecise code. As Hiroku puts it, “only three countries I experienced. no time to learn three different languages.”

Hiroku understands that Knut is drawn to her for the linguistic inventiveness of Panska: “I could sense [Knut’s] libido rushing not toward me but toward my language.” The book is not a love story between Knut and Hiruko (the two become close friends), but an elegy to the power of language and its ability to evolve along with the changing world. Though the tale is not life-affirming, it is language-affirming. Near the end of the book, Hiruko explains how Panska makes her feel more connected to those who pay attention to it, like Knut: “Though it’s spontaneous and far from perfect, as the words stream along the wrinkles of my memory, picking up every sparkling thing, no matter how small, they take me to magical faraway places. Only Panska can take me there, not my native language.” There, from the cracks between nationalities, the holes in the globe created by climate disaster, sprouts the language of connection. In a world where the “mother tongue” is lost or forgotten, Knut and Hiroku make a home together inside a new grammar.

*

In many ways, connection through language is what Au’s main character sets out to find with her mother by going to Japan in Cold Enough for Snow. In contrast to Tawada’s broad, world-building brushstrokes, Au’s novel is subtle and emotionally-driven, concerned with the borders between people, the present moment and memory, memory and dreams.

Au’s intimate, confessional form may tempt the reader to locate her within the tradition of contemporary “autofictionalists.” However, there is a larger, more complex history at play in Cold Enough for Snow. Long before Knausgaard, Lerner, or Cusk, Japanese writers like Katai Tayama, Naoya Shiga, and Minae Mizumura were writing a genre called shishōsetsu, or the “I-novel,” confessional stories in which the protagonist and the author are conflated. Like Au’s novel, shishōsetsu involves “the writer [probing] innermost thoughts or attitudes toward everyday events in life.” This genre, which some date back to The Pillow Book (1002) by lady Sei Shōnagon, was often used by twentieth century Japanese authors to explore the tensions between the East and the West, and, accordingly, between the traditional and the modern worlds. As the critic Edward Fowler described shishōsetsu, “Its personal orientation makes it a thoroughly modern form; yet it is the product of an indigenous intellectual tradition quite disparate from western individualism.”

By employing this self-revealing form, Au sets her book at a literary borderline between the West and the East, a tension reflected in the contrast between the narrator’s western upbringing (presumably in Australia, Au’s native country, though it is left unspecified), and her mother’s Hong Kong origins. She is explicit about this divide, saying: “I had chosen Japan because I had been there before, and although my mother had not, I thought she might be more at ease exploring another part of Asia. And perhaps I felt that this would put us on equal footing in some way, to both be made to be strangers.” Japan for her represents a place of equal foreignness and nativeness.

The country also represents the desire to create a shared language with her mother—a Panska, so to speak—of their own. She hopes to achieve this by inviting her mother into the world of art, in which Au's narrator has made a home for herself. She illustrates the allure of this world when describing a Monet exhibition: “Each still… showed the world not as it was but some version of the world as it could be, suggestions and dreams, which were, like always, better than reality and thus unendingly fascinating.” What art holds for her is not the promise of knowledge, but a window into a dreamscape, a world of imagination, of memory—a world in which she feels at home. Her own language, even, reflects this dreamlike quality. She is simple, legible, and textural, as if she herself is creating an elegant object for anyone to view.

Yet the world of art, which feels more “real” to her than anything else, is also where she most dramatically fails to share a language with her mother. She describes the two of them looking at Monet together:

I said that… I understood the pressure of feeling like you had to have a view or opinion, especially one you could articulate clearly, which usually only came with a certain education. This, I said, allowed you to speak of history and context, and was in many ways like a foreign language. For a long time I had believed in this language, and I had done my best to become fluent in it. But I said that sometimes, increasingly often in fact, I was beginning to feel like this kind of response too was false, a performance, and not the one I had been looking for… It was all right, I said, to simply say if that was so. The main thing was to be open, to listen, to know when and when not to speak.

The end of the chapter comes immediately after this monologue, like a brick of silence, implying that the narrator’s mother doesn’t respond, or if she does, that it is not the kind of response that fulfills the narrator’s desire for mother-daughter bonding. Perhaps the mother doesn’t respond in the way her daughter craves because of their language divide. The narrator reflects, “I thought too of how my mother’s first language was Cantonese, and how mine was English, and how we only ever spoke together in one, and not the other.” But in another way, there is a divide in emotional language: The dream world that has become so significant to the narrator’s inner life is a foreign tongue to her mother, too firmly associated with preconceived ideas about who can talk about art. Unlike Tawada’s Panska, Au’s narrator invites her mother into her world, but her mother remains firmly at the threshold, trembling, uncertain.

*

Monet represents tensions—of belonging and foreignness, of the East and the West—that deeply inform both Cold Enough for Snow and Scattered All Over the Earth. A French Impressionist at the turn of the century, Monet was also a key figure in Japonism, a movement in which western artists like Manet and Van Gogh took inspiration from the Japanese aesthetic. Japonism led European artists to focus on elements of painting like “harmony, symmetry, and empty spaces,” which “[provided] artists with a new possibility of alluding to hidden meanings or sentiments.” In one scene in Scattered All Over the Earth, Knut the linguist watches a TV program in which Monet travels from place to place—Pourville, Christiania, and then to Mt. Kolsass in Norway, in front of which he sets up his easel, only to paint Mt. Fuji, the subject of so many famous Japanese paintings. For Tawada, Monet’s life represents the blurring of national boundaries and the subtle, centripetal pull that Japan has, even in its absence, simply by imagining it, as all the characters do throughout the book. Scattered All Over the Earth is about the Japan that exists in the mind’s eye of the west, the mythical Japan, the space where art or language, like Panska, is born between cultures.

Au’s narrator does not engage with this history. “I knew very little of Monet... I did not know much about the era in which we had painted, or the famous techniques he had pioneered,” she says. It’s not that the historical, geographical tensions aren’t present for Au, but they are more subtle and unspoken. They are, like the long tradition of Japanese autofictionalists, silent infrastructure that gives her novel secret depths, simmering with unspoken meaning. For instance, when she and her mother are served noodles at a restaurant near Osaka, she reflects that “the same pattern must have once existed on elaborate plates and tableware during a certain period in history.” And so while gesturing to the historical context, she references no dates or figures. She instead spends much of the page describing the childhood memory that the bowl evokes and capturing the sensory experience of it: The “large bowl is white on the inside, but decorated with a complicated, dense pattern of dull watermelon pinks and greens and yellows on the outside.” Au leaves the history like a skeleton, supporting the structure silently beneath the smooth textures of skin. Each of her images feels supported in this way—not didactic or clear, but containing a deeper resonance than is being explained. What’s more, by refusing to delve into the historical background, she actually mimics the emphasis on empty space—on absence and unspoken feelings—in traditional Japanese paintings, and in the Japonism of Monet.

Part of what defines both books—and the success of their respective projects—is scale. Scattered All Over the Earth is driven by quantity—many characters are squished into the pages, and broad historical and cultural reflections never leave enough room for any one story to be fleshed out. The effect is a novel that feels, well, a bit scattered. On the other hand, Cold Enough for Snow’s is defined by its small scale, driven by the details of life in its absolute present moment. Au’s flashbacks are more concerned with the patterns on bowls, the texture of fabrics, or the light through a “canopy of leaves,” than the sequence of events. Her language comes from a different logic of attention: One that skims along the textures of life, floating from one association to another; she finds connections not in historical causation, but in the way walking home after a swim recalls the same feeling as looking at Impressionist paintings. And if the narrator doesn’t succeed in bonding with her mother, Au succeeds in connecting to the reader with her subtle language and elegant way of looking.

In many ways, it took reading Scattered All Over the Earth for me to understand exactly how to describe my experience with Au’s language in Cold Enough for Snow. In Tawada’s descriptions of Panska, there is something luminous and erotic about the language: “The homemade language Hiroku spoke was like Monet’s water lilies. The colors, shattered into pieces, were beautiful but painful.” And yet, while Scattered All Over the Earth has poetic moments, its language tends towards the blunt and straightforward, for it is a world-building and character-describing endeavor. However, the effect that Panska has on Knut perfectly encapsulates the effect that Au’s language had on me: “Listening to those strange sentences, I stopped worrying about whether or not they were grammatically correct, and felt I was gliding through water.” This comparison reveals that what these books discuss is less significant than how they discuss it. They represent two sides of the same coin, complementing each other's perspectives: Tawada takes a bird’s eye view and surveys the unfamiliar landscape of globalization, while Au—unconcerned with physical disappearances, or topographical shifts—portrays the emotional absences and missed connections of daily life. It's the difference between an anthropologist's lens and a poet's, or between reading a book about Monet and being inside the painting. While there is valuable knowledge to glean from representing a broad, historical landscape, in this case I prefer to be next to the water lilies, experiencing each brush stroke as if it floats up next to me, along with the associative past and the uncertain future.